UPDATE 9.6.22: Lori Ioannou of The Wall Street Journal calls dividend stocks the “new darling on Wall Street.” She writes:

These securities are considered a good buffer during times of market volatility. They also are seen as an inflation hedge, considering that S&P 500 dividend growth has outpaced inflation since 2000.

UPDATE 7.5.22: The state of the economy is shaky. Inflation is soaring, faddish bets like cryptocurrencies are melting down, and overall Americans are not happy with the way things are going. Those indicators are all signs that troubling times may be ahead. It’s important in times like these to look back at the staid wisdom of those who came before and remember the foundational lessons that keep you headed in the right direction. One of the best pieces ever written on investing is Rich Man, Poor Man by Richard Russell. I encourage you, in these fragile times, to reread this bit of deep investing knowledge and adjust your approach accordingly.

Originally posted November 29, 2019.

This is one of my favorite investment pieces by the late Richard Russell:

Rich Man, Poor Man

By Richard Russell

The most popular piece I’ve published in 40 years of writing these Letters was entitled, “Rich Man, Poor Man.” I have had dozens of requests to run this piece again or for permission to reprint it for various business organizations.

Making money entails a lot more than predicting which way the stock or bond markets are heading or trying to figure which stock or fund will double over the next few years. For the great majority of investors, making money requires a plan, self-discipline and desire. I say, “for the great majority of people” because if you’re a Steven Spielberg or a Bill Gates you don’t have to know about the Dow or the markets or about yields or price/earnings ratios. You’re a phenomenon in your own field, and you’re going to make big money as a by-product of your talent and ability. But this kind of genius is rare.

For the average investor, you and me, we’re not geniuses so we have to have a financial plan. In view of this, I offer below a few items that we must be aware of if we are serious about making money.

Rule 1: Compounding: One of the most important lessons for living in the modern world is that to survive you’ve got to have money. But to live (survive) happily, you must have love, health (mental and physical), freedom, intellectual stimulation — and money. When I taught my kids about money, the first thing I taught them was the use of the “money bible.”

What’s the money bible? Simple, it’s a volume of the compounding interest tables.

Compounding is the royal road to riches. Compounding is the safe road, the sure road, and fortunately, anybody can do it. To compound successfully you need the following: perseverance in order to keep you firmly on the savings path. You need intelligence in order to understand what you are doing and why. And you need a knowledge of the mathematics tables in order to comprehend the amazing rewards that will come to you if you faithfully follow the compounding road. And, of course, you need time, time to allow the power of compounding to work for you. Remember, compounding only works through time.

But there are two catches in the compounding process. The first is obvious – compounding may involve sacrifice (you can’t spend it and still save it). Second, compounding is boring — b-o-r-i-n-g. Or I should say it’s boring until (after seven or eight years) the money starts to pour in. Then, believe me, compounding becomes very interesting. In fact, it becomes downright fascinating!

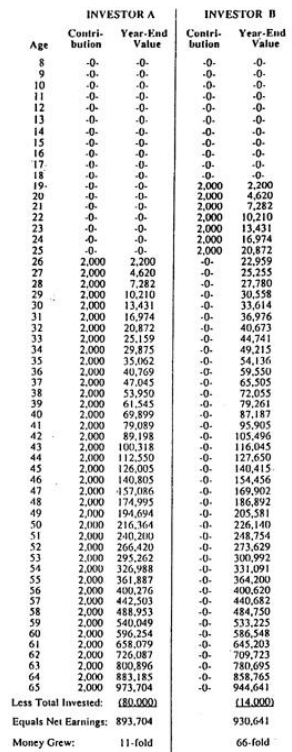

In order to emphasize the power of compounding, I am including this extraordinary study, courtesy of Market Logic, of Ft. Lauderdale, FL 33306. In this study we assume that investor (B) opens an IRA at age 19. For seven consecutive periods he puts $2,000 in his IRA at an average growth rate of 10% (7% interest plus growth). After seven years this fellow makes NO MORE contributions — he’s finished.

A second investor (A) makes no contributions until age 26 (this is the age when investor B was finished with his contributions). Then A continues faithfully to contribute $2,000 every year until he’s 65 (at the same theoretical 10% rate).

Now study the incredible results. B, who made his contributions earlier and who made only seven contributions, ends up with MORE money than A, who made 40 contributions but at a LATER TIME. The difference in the two is that B had seven more early years of compounding than A. Those seven early years were worth more than all of A’s 33 additional contributions.

This is a study that I suggest you show to your kids. It’s a study I’ve lived by, and I can tell you, “It works.” You can work your compounding with muni-bonds, with a good money market fund, with T-bills or say with five-year T-notes.

Rule 2: DON’T LOSE MONEY: This may sound naive, but believe me it isn’t. If you want to be wealthy, you must not lose money, or I should say must not lose BIG money. Absurd rule, silly rule? Maybe, but MOST PEOPLE LOSE MONEY in disastrous investments, gambling, rotten business deals, greed, poor timing. Yes, after almost five decades of investing and talking to investors, I can tell you that most people definitely DO lose money, lose big time — in the stock market, in options and futures, in real estate, in bad loans, in mindless gambling, and in their own business.

RULE 3: RICH MAN, POOR MAN: In the investment world the wealthy investor has one major advantage over the little guy, the stock market amateur and the neophyte trader. The advantage that the wealthy investor enjoys is that HE DOESN’T NEED THE MARKETS. I can’t begin to tell you what a difference that makes, both in one’s mental attitude and in the way one actually handles one’s money.

The wealthy investor doesn’t need the markets, because he already has all the income he needs. He has money coming in via bonds, T-bills, money market funds, stocks and real estate. In other words, the wealthy investor never feels pressured to “make money” in the market.

The wealthy investor tends to be an expert on values. When bonds are cheap and bond yields are irresistibly high, he buys bonds. When stocks are on the bargain table and stock yields are attractive, he buys stocks. When real estate is a great value, he buys real estate. When great art or fine jewelry or gold is on the “give away” table, he buys art or diamonds or gold. In other words, the wealthy investor puts his money where the great values are.

And if no outstanding values are available, the wealthy investors waits. He can afford to wait. He has money coming in daily, weekly, monthly. The wealthy investor knows what he is looking for, and he doesn’t mind waiting months or even years for his next investment (they call that patience).

But what about the little guy? This fellow always feels pressured to “make money.” And in return he’s always pressuring the market to “do something” for him. But sadly, the market isn’t interested. When the little guy isn’t buying stocks offering 1% or 2% yields, he’s off to Las Vegas or Atlantic City trying to beat the house at roulette. Or he’s spending 20 bucks a week on lottery tickets, or he’s “investing” in some crackpot scheme that his neighbor told him about (in strictest confidence, of course).

And because the little guy is trying to force the market to do something for him, he’s a guaranteed loser. The little guy doesn’t understand values so he constantly overpays. He doesn’t comprehend the power of compounding, and he doesn’t understand money. He’s never heard the adage, “He who understands interest — earns it. He who doesn’t understand interest — pays it.” The little guy is the typical American, and he’s deeply in debt.

The little guy is in hock up to his ears. As a result, he’s always sweating — sweating to make payments on his house, his refrigerator, his car or his lawn mower. He’s impatient, and he feels perpetually put upon. He tells himself that he has to make money — fast. And he dreams of those “big, juicy mega-bucks.” In the end, the little guy wastes his money in the market, or he loses his money gambling, or he dribbles it away on senseless schemes. In short, this “money-nerd” spends his life dashing up the financial down-escalator.

But here’s the ironic part of it. If, from the beginning, the little guy had adopted a strict policy of never spending more than he made, if he had taken his extra savings and compounded it in intelligent, income-producing securities, then in due time he’d have money coming in daily, weekly, monthly, just like the rich man. The little guy would have become a financial winner, instead of a pathetic loser.

RULE 4: VALUES: The only time the average investor should stray outside the basic compounding system is when a given market offers outstanding value. I judge an investment to be a great value when it offers (a) safety; (b) an attractive return; and (c) a good chance of appreciating in price. At all other times, the compounding route is safer and probably a lot more profitable, at least in the long run.

Here’s how you can put Rich Man Poor Man to work for your grandchildren:

The short answer is, early. The earlier you can start saving for your grandchild, the greater the impact you’ll have on their life.

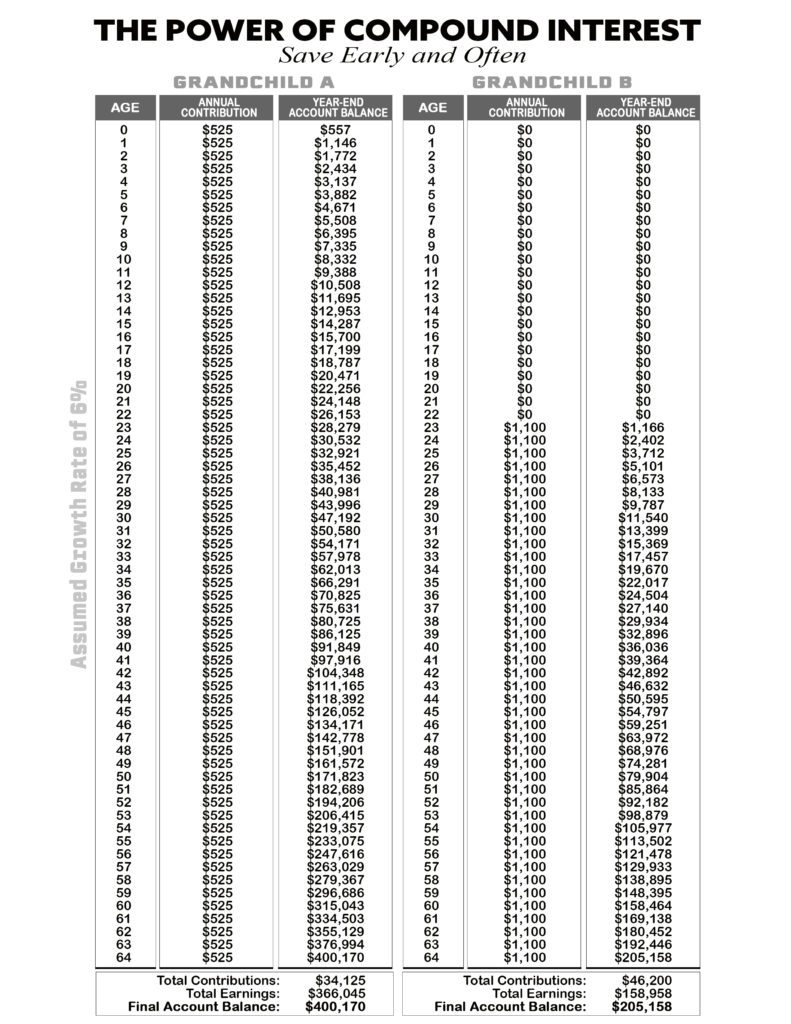

Take a trip with me. Let’s say you help a grandchild get into the savings game when they’re born by contributing $525 per year to an account you establish for them. (I favor UGMAs for this purpose). You diligently save each year for her first 21 years.

Then when she turns 22, she continues along the same path, saving $525 on her own each year until she’s 64.

Look at my table below to compare her success to someone who begins his investment savings at age 22 at double the savings rate of your granddaughter, saving $1,100 each year. Even though he’s saving twice as much each year, when he turns 64 he’ll have half as much as your granddaughter simply because you helped put time on her side with your early generosity (I’ve used a long-term expectation for stocks of 6% growth per year).

So, how do you save money for your grandchild? Easy, put time on their side.