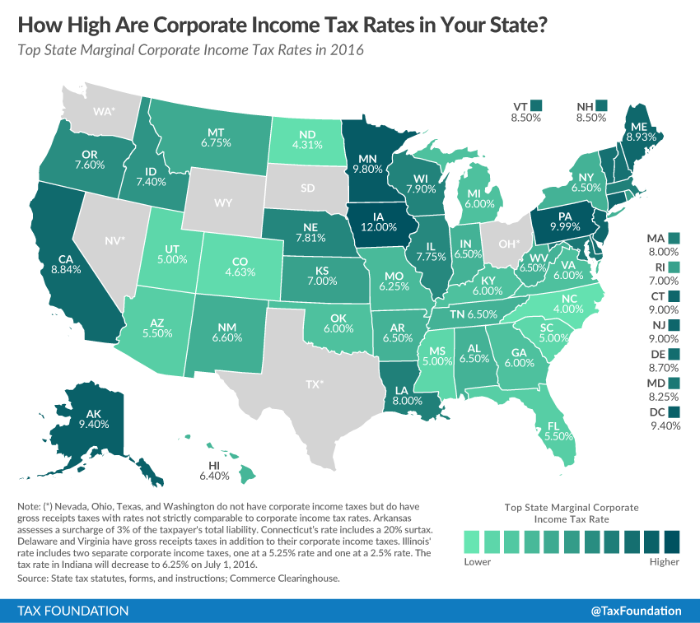

You get a real clear picture looking at this map (from the Tax Foundation) on corporate income tax rates by state as to why so many businesses are moving, for example, from California to Austin, Texas. Businesses go to where they’re well-treated. For start-ups, meaning entrepreneurs, that means moving from state to state. For global players it’s moving from country to country.

The latest hit to American business comes from Johnson Controls’ merger with Tyco International, headquartered in Ireland. The other real kicker here is it that JC had plenty of your (taxpayer) help to stick around.

Johnson Controls Inc. was as patriotic as they come back in 2008, when the U.S. auto industry was teetering on bankruptcy and the Glendale-based maker of car parts knew it desperately needed help from U.S. taxpayers.

The company’s president at the time, Keith Wandell, didn’t hesitate to ask Congress to support the massive government bailout that ultimately rescued two major U.S. automakers, along with uncounted businesses that provide parts and services to them.

“It saved a whole lot of suppliers that would have gone out of business,” said Steve Roell, then Johnson Controls’ chief executive.

And the auto bailout wasn’t the only government handout to benefit Johnson Controls in the past decade. In 2010, for example, it received $299 million from the Energy Department to ramp up production of hybrid batteries. The state of Michigan awarded it millions of dollars for the same project.

Our friend, Dan Mitchell, senior fellow at the Cato Institute, writes in Fortune:

In the words of the late Yogi Berra, it’s déjà vu all over again. The merger of Johnson Controls JCI -1.90% and Tyco International has triggered a lot of whining and complaining in Washington because the combined company will be based in low-tax Ireland instead of high-tax America.

Not that anyone should be surprised. In almost all cases of high-profile, cross-border mergers, such as the Pfizer-Allergan deal last year and the Burger King- Tim Horton deal the previous year, the new company chooses to be domiciled where there’s better tax laws.

Some U.S. politicians respond to these mergers with demagoguery about “economic treason,” but that’s silly. These corporate unions are basically the business version of a couple in a long-distance relationship that decides to live where the economic outlook is brighter after getting married.

The bottom line is that U.S.-domiciled firms are being forced to compete while burdened with a tax code that is uniquely destructive.

So instead of blaming the victims, the folks in Washington should do what’s right for the country by trying to deal with the warts that make America’s tax system so unappealing for multinational firms.

There are two main problems. The first is that the United States now has the world’s highest corporate tax rate. With a 35% levy from Washington, augmented by smaller state corporate taxes, the combined burden is more than 39%.